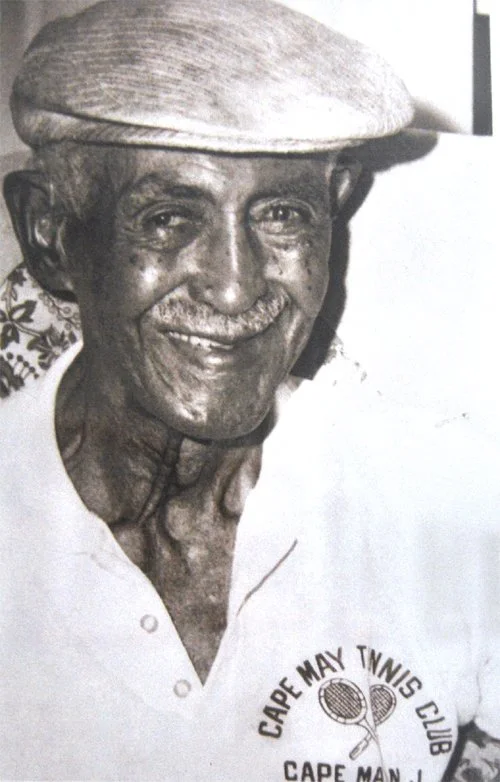

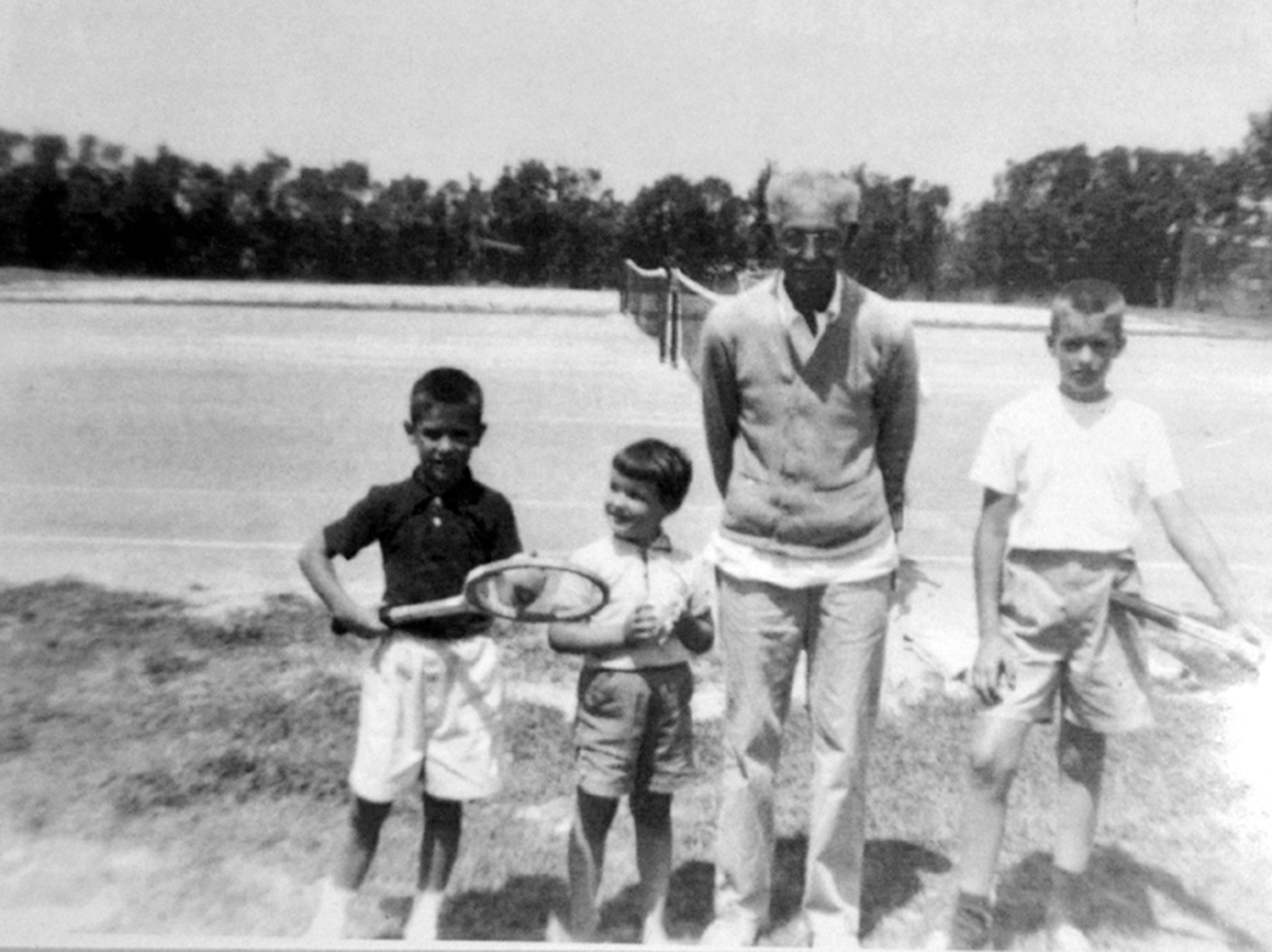

Influencing three generations of students.

Reprinted from The Cape May Star and Wave, July 31, 1997, on the occasion of the 125th anniversary of William J. Moore’s birth. By Molly Tully

He attended the festivities honoring his 100th birthday on a stretcher. But unlike most centenarians who might be expected to be suffering from normal deterioration, William J. Moore’s distress was due to a fall on a tennis court the previous week when he had posed for photographers anxious to publicize the forthcoming event. He tripped, fell, broke his hip and was rushed off to the hospital, only to insist on being returned on a stretcher to be present for the celebration which devoted citizens of Cape May, New Jersey, and members of the Tennis Club had planned for weeks. They were dedicating the courts to him, henceforth to be known as the William J. Moore Tennis Center. He was their friend, their teacher, the organizer of their tennis club and their pro for over 50 years.

At the time of his death, less than a year later, in June l973, William Moore had accomplished more than most human beings dream of in a lifetime. More than the oldest living and first black tennis pro in America, he was a remarkable human being, a dedicated teacher, an inspiring leader in his community, and – perhaps most important – a devoted husband and father.

Born in 1872 of parents who had been released from slavery after the Emancipation, he grew up in West Chester, Pennsylvania. The first black to graduate from the local high school, he went on to Howard University, graduating from their Normal School in 1892, and began a teaching career which covered fifty-three years and included at least three generations of black youth in West Cape May.

He didn’t take up tennis until he was in his thirties and not only perfected the technique but worked out a unique teaching method which was later published in a manual still recognized as a major contribution to teaching the game.

In his spare time he wrote articles for the Cape May County Geographic Society and the County Historical Society on conservation, nature, early Negro settlers in the County and other subjects.When he was honored by Howard University during its centennial celebration in June 1967, for his outstanding achievements in education and athletics, he was only incidentally the oldest living alumnus. In 1969, he received a plaque from the Middle States Lawn Tennis Association at the Spectrum in Philadelphia for “loyal and meritorious service to tennis.” And in 1972, he was honored by the New Jersey Education Association for his contributions to education.

But all this recognition, these honors, these awards, don’t begin to capture the depth of William Moore as a human being. Interested in everything around him, and with a love and appreciation of his fellow man, his family, his students and the country which had given him so many opportunities, his life was an example of what one man can achieve in a lifetime.

William J. left behind a lively and fascinating autobiography in which he tried to enumerate the important sequences in his life. Reading it, one can feel the sparkle and depth of his character. Growing up in the small, predominately Quaker town of West Chester was a circumstance to which he attributes a great deal of his success. “I never felt any color line in West Chester,” he states.” “This gave me a chance to develop without the frustration of race prejudice. I went everywhere and joined in everything that my playmates did.”

Because his father was sexton of the First Presbyterian Church there, and the family lived on the church grounds, his playmates were white, upper middle class, well educated children of professionals. His parents determined that he should have a good education. As the oldest of three and quite a bit older than the next two, he received the devoted attention of parents and grandparents who “furnished me with a comfortable wholesome home life and a heritage of spotless character to emulate, and who insisted I take full advantage of educational opportunities and meet their standards. They impressed upon me that school was my job, that no studies were too hard – and “in all matters the teacher was always right!”

It was a happy childhood with ample opportunity for play, and exploring the out-of-doors. During the summer months, William and his “gang” of

playmates explored nearby Brandywine Creek, wandering for miles up and down its shores, building boats, swimming, observing wildlife, collecting rocks, leaves, bird eggs and butterflies, later identifying their specimens from books or professional acquaintances.

From his paternal grandfather, who had escaped from slavery via the Underground Railroad, he learned the names of all the constellations which was a big help later at Howard. He recalls an incident that happened one evening as he was crossing the campus. An astronomy professor was giving a star-gazing lecture, but was having trouble putting a nder on the Beehive cluster. “Can I help you?” asked Moore, and immediately found the spot. This chance encounter led to many hours of extracurricular physics and chemistry in the professor’s laboratory. “Grandfather was a great stickler for character often showing with pride his testimonials and recommendations from prominent citizens for whom he had worked. He impressed upon me, his namesake, my duty to live up to the standards of the family name.”

On Sundays, William helped to pump the church organ, coming into contact with much of the best of church and classical music. He was an avid reader and “due to the prevalence of libraries in the town, and also my wide circle of friends, I always had access to an unlimited supply of books from which to choose.” He dipped into such classics as Cooper, Irving, Holmes, Whittier, Dickens, Scott, Lytton, Thackery and Longfellow. Learning was fun, so it was natural that he would want to continue his education after high school. Through a member of the congregation, he was encouraged to attend Howard University. There he was exposed to a group of teachers and subjects which opened up new horizons to him. West Chester had prepared him well, and he frequently found himself more knowledgeable than some of his teachers. In addition, “Washington was an exciting place in which to live, with museums to explore, lectures and concerts to attend, and new friendships to develop.” At that time there wasn’t so much prejudice in Washington as came later… The only way I knew about segregation was from talking to my classmates from the South.” It was there he met and was inspired by many of the country’s black leaders of the time. Besides having a scholarship, William Moore worked part-time in the Dean’s office to help pay the cost of room ($15 a year) and board ($8 a month). Tuition was free in the Teaching Department.

But it was more than the ambiance of his home town or the inspiration of an excellent education which accounted for William J. Moore’s dedication to high ideals during his whole lifetime. It was in his blood. His father had been born in slavery and served as a slave in the Army before being released and moving North after the Civil War. On his mother’s side, his grandmother was part Indian and had been raised on a large Virginia plantation where she had absorbed the culture and values of Southern aristocracy. It was from her that he inherited also his instinctive love of nature. His teaching always included walks through the woods and swamps of Cape May’s countryside identifying the flora and fauna for his pupils.

Moore had not intended to settle in Cape May. After turning down a fellowship from Howard (“I felt my parents had supported me long enough”) he accepted a teaching job in Greenspring, Delaware for a year, then spent a year teaching in West Chester. He had been offered a job in Texas, but accepted the Cape May job to be nearer home, intending to stay only a year and then move to Texas. But he saw a challenge in the situation in Cape May. Here were black children who had virtually been ignored by the system, and a growing black population, imbued with the feeling that education was important. William was anxious to work out some theories he had for a first class elementary school.

His mentor in this experiment was a man named William E. Tranks, a self- educated man who was widely read and a disciple of Henry George. For years he had advocated home ownership for blacks so they would have a say in local politics, and many of the residents did own their homes with enough land to raise poultry and vegetables. Many of the blacks who had settled in Cape May came from the South, having been freed after the Emancipation. Since many of them had come in the summers with Southern families to this elegant resort in the 1800’s, it was natural that they would stay on here after the Civil War.

When Moore began teaching in Cape May in 1895, he was assigned one room in the West Cape May School where he taught eight grades of black children. He was determined that blacks learn more than the three R’s. He instilled in them a sense of pride, not only in their black heritage, but in themselves as individuals, and as citizens of their great country. He used outlines of black history which today would be called Black Studies, learning about important achievements of blacks throughout history.

Gradually more and more of his pupils went on to high school and college to the intense pride and delight of their parents. As one mother remarked, “If Mr. Moore said, ‘go to college’ we felt we had to send them.” In high school they won many honors and were acclaimed by principals and teachers as well prepared students.

He achieved a real school spirit and pride among the students. As he says in his autobiography, “All this as a result of teaching that we, as Americans, could do anything that any other Americans could do; that it was a disgrace to fail or quit when studies were hard, and that parents and the community expected West Cape May students to succeed.”

One day as they finished singing “America” – having recently been studying the history of the Pilgrims, a pupil asked what” “we had to be proud of.” To inspire him and others William wrote:

“We too have a right to sing ‘My Country.’ Old Spanish records state that we were with Columbus and Coronado. History records that we were here at Jamestown (1619) before the Pilgrims landed (1620). From then on it was our labor that changed the South from a primitive wilderness into the garden spot of America. Our labor created practically all the wealth of the South on which was based that culture of which they boast. We cut down the forests, drained the swamps, cultivated the crops and nursed and reared the families of the Southern Aristocrats. We have fought bravely in all the wars. On the wall of the Capitol in Washington is a picture of Commodore Perry on Lake Erie, showing a colored sailor in his crew. We have never had a traitor! On the contrary, we have loyally contributed our efforts from slave times until now, toward every movement to make America great.”

Moore continued, “Yes, we can sing My Country with pride. We came with the rst discoverers, we have been here ever since, and we’re going to stay here.”

It was during his first winter in Cape May that he noticed a particularly beautiful voice in the choir at the Franklin Street Methodist Church one Sunday. Susie Smothers had come to Cape May from Mount Winents, now a suburb of Baltimore, with a family which had summered there, and stayed on to work for Dr. Physick in the lovely estate which now adjoins the present tennis club. She and William Moore were married the following year.

As a family man, William was a devoted husband and father. His wife, by his own description, was “quiet, cultured, stable and good natured… Her love for her family was boundless, and her influence on their development and lives was immeasurable.” Even years later Lavinia and Amaleta, the two daughters (both active in education, one as principal of a school in Detroit, the other a psychology professor at Hampton Institute in Virginia) remember their mother as “always being there.” She was there when they got home from school, always knew where and when they came and went, and never retired until they were all home. “So well did they know this,” says William in his description of her, “that if some of the boys were out a little late they always brought Mother some ice cream as a sort of apology for their tardiness.”

Of his nine offspring, seven went to college; six went on for advanced degrees all of whom followed him in a career of teaching. Three survive today: Amaleta and James Alexander who reside n West Cape May and Silvius who remains at Hampton University where all three had teaching careers. The others: Hiram, Wilbur, Frank, William, Osceola and Lavinia have passed away, but all spent most summers and retirement years back home in West Cape May.

It was always assumed in the Moore family that you would go to college. Lavinia tells of listening to her older brother Wilbur talk about his life at Howard, and how as a member of the football team he had traveled to West Virginia University to play. He described the beauty of the countryside there with great enthusiasm. When Lavinia was asked by classmates where she was going to college, she thought quickly and blurted, “Why, West Virginia University!” She did indeed end up there mainly because they gave Moore the best exchange rate for his scrip with which a schoolteacher was paid in those days of the Depression.